31-byte code-chunker

Background reading

To get a proper background on where this code chunker fits into stateless Ethereum, read the Trees introductory chapter and the Code chunking section of Data encoding.

How does it work?

Let’s look at the following example code:

PUSH1 0x42 # 6042

PUSH1 0x00 # 6000

MSTORE # 52

PUSH2 0x0001 # 610001

PUSH2 0x0002 # 610002

ADD # 01

MSTORE # 52

PUSH20 0x0000000000000011223344556677889900115b33 # 73<...>

RETURN # F#

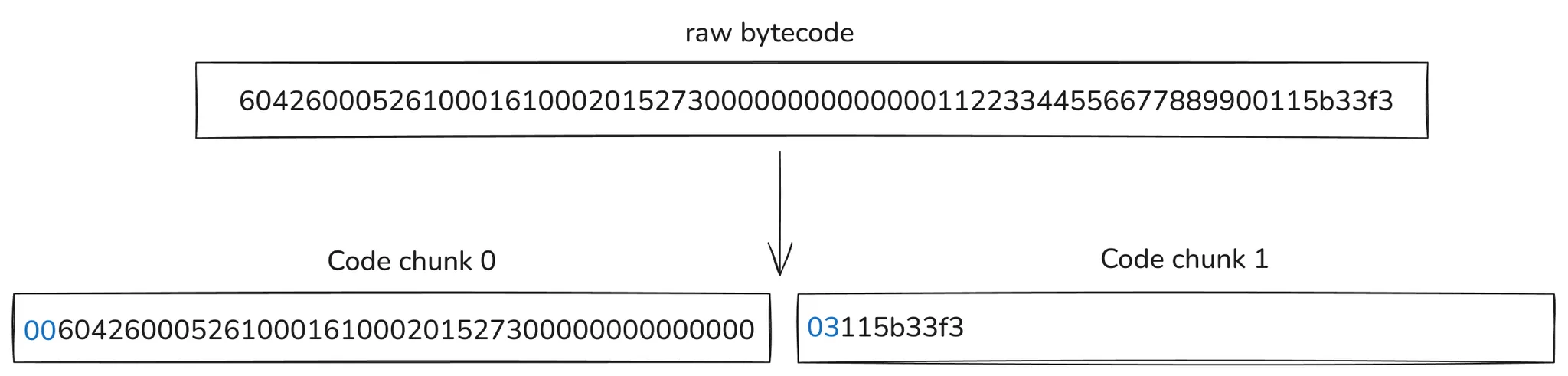

The following diagram shows how the code is chunkified:

Recall that an account code is a blob of bytes containing all the contract instructions. The goal of the code chunker is to:

- Output a list of 32-byte blobs, which will be stored as tree leaves.

- Given a code chunk without any extra information, an EVM interpreter should be able to detect if a JUMP to any byte in this chunk is valid.

Requirement 1 is easy to understand since each tree leaf stores 32-byte blobs. We can appreciate this requirement being fulfilled since the presented Python code returns a Sequence[bytes32].

Requirement 2 emerges from the fact explained in the Code chunking section in the current chapter. Since any JUMP(I) can jump to any byte offset in any chunk, an EVM interpreter should be able to detect if this jump is (in)valid without any further information than the code chunk itself.

The way the 31-byte code chunker resolves this is as follows:

- The account bytecode is partitioned into slices of 31 bytes in size.

- The first byte contains the number of bytes starting from the 31-byte slice that account for PUSHDATA, i.e., a previous

PUSH(N)instruction data.

In the diagram, this first byte is shown in blue. Note that the second code chunk indicates that the first 3 bytes correspond to the previous PUSH20 instruction. This allows the stateless client to note that the 0x5b byte in this code chunk isn’t a valid JUMPDEST!

Using this 1-byte information at the start of the code chunk allows the EVM interpreter to detect if any jump to an offset in the code chunk is valid, i.e., 0x5B is an actual JUMPDEST. Given that the bytecode length of a contract is N bytes, we know that the number of required chunks is ceil(N/31). If you’re interested in a Python implementation of the chunker, see the second code snippet here.

The design of this code chunker is very simple, but the encoding efficiency is not optimal. For example, if a bytecode doesn’t contain any PUSH(N) instruction, then we know any JUMP(I) is valid, but we’re still only encoding 31 bytes of actual code in 32-byte code chunks. Similarly, if this is an EOF contract, by construction, we know all jumps are valid; thus, we don’t require the extra byte. Soon, we’ll describe other code chunkers with different tradeoffs.